Tag: shared decisionmaking

What about the patient?

My 85-year-old mother was recently hospitalized and the experience was a great example of how far our healthcare system has come and how far it still needs to go.

My 85-year-old mother was recently hospitalized and the experience was a great example of how far our healthcare system has come and how far it still needs to go.

The good news is that she only required 2 days in the hospital, had no complications, felt dramatically better at discharge and felt “cared for” during her hospitalization.

Here are a few things that were great: everyone we encountered was very nice, she received a printed record of her hospitalization when she was discharged (it didn’t contain much useful information but that’s a separate issue) and she was helped to sign up for access to the hospital portal so she could review her records online.

In short, the customer service was excellent. However, there were 2 important failures to see things through her eyes – one on admission and one on discharge.

The power of placebos

Lots of people talk about the placebo effect but what exactly is it?

Lots of people talk about the placebo effect but what exactly is it?

The most reliable clinical studies compare a treatment that is being tested with a fake treatment (called a placebo). Generally, half the people in the study get the treatment and half get the placebo and the then the two groups are compared. In the case of pills the placebo is often a sugar pill. Researchers can even test the effectiveness of a surgical procedure by comparing it with a sham or fake procedure. In these studies (called randomized controlled trials or RCTs), patients (and their healthcare teams) don’t know who is getting the pill or procedure being studied and who is getting the placebo. The reason for this is that patients sometimes get better when they are given a placebo because they believe they will get better (called the “placebo effect”) or because their disease got better on its own.

So can patients get better just by believing they will get better? And can doctors actually prescribe placebos to help people get better?

Patients and parents as partners – part II

What if hospitals worked together to improve the care they deliver to patients with a particular disease (instead of competing with each other)? What if these hospitals considered patients and families their teachers and members of their teams? I’ve written before about the magic of the ImproveCareNow (ICN) network but even I am amazed at how quickly the interest in patients and parents as partners has grown within the network.

What if hospitals worked together to improve the care they deliver to patients with a particular disease (instead of competing with each other)? What if these hospitals considered patients and families their teachers and members of their teams? I’ve written before about the magic of the ImproveCareNow (ICN) network but even I am amazed at how quickly the interest in patients and parents as partners has grown within the network.

Paying patients for their expertise

Thanks to the work of organizations like the Society for Participatory Medicine and patient advocates like e-patient Dave, the voice of the patient is being heard. And I’ve written before about organizations like the ImproveCareNow network where patients and families are treated as equal partners in quality improvement efforts.

Thanks to the work of organizations like the Society for Participatory Medicine and patient advocates like e-patient Dave, the voice of the patient is being heard. And I’ve written before about organizations like the ImproveCareNow network where patients and families are treated as equal partners in quality improvement efforts.

I love that patients and families are being recognized for their expertise and that healthcare organizations are starting to involve patients as team members from the beginning of projects. I also love that organizations like PCORI (Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute) are recognizing the importance of asking patients the research questions and outcomes that are most important to them.

So this is all really good, right? Yes, but…

Parents as partners

Imagine a group of medical centers that share ideas and borrow from each other in order to improve the quality of the care they deliver. Imagine care teams where doctors, nurses, nutritionists, other health professionals and researchers work side by side with pediatric patients and their parents to figure out the best ways to deliver care. Imagine a healthcare conference where patients and parents are the teachers with doctors listening attentively and asking questions.

Imagine a group of medical centers that share ideas and borrow from each other in order to improve the quality of the care they deliver. Imagine care teams where doctors, nurses, nutritionists, other health professionals and researchers work side by side with pediatric patients and their parents to figure out the best ways to deliver care. Imagine a healthcare conference where patients and parents are the teachers with doctors listening attentively and asking questions.

I just returned from the ImproveCareNow Spring Learning Session where I saw all of this firsthand. ImproveCareNow (ICN) is a network of 64 (65 as of yesterday) care centers whose mission is to

Are screening tests good for you?

If we had a serious disease, we’d like to learn about it before we even had symptoms (so we could get started on treatment). And most of us would like to know if we were at risk of developing a serious disease (so we could make changes to prevent the disease). Right?

Two recent articles in the NY Times point out the problems with screening tests.

Who makes the best medical student?

As I begin my 4th year interviewing prospective medical students, I am reminded of how challenging it is to figure out which applicants will possess all of the characteristics that I would want in my own doctor.

There is little question that we need to rethink the way we educate medical students to meet the needs of a changing healthcare system. Medicine is no longer a paternalistic practice where the doctor tells the patient what to do. Not only are patients becoming more empowered to participate in the own care, but they also have information at their fingertips about their own conditions and can access online discussion groups to talk with other patients about their shared experiences. The blog Wing of Zock looks at innovative ways to redesign medical education.

Does food cause inflammation?

I am fascinated by food – what makes us eat the food we eat and how it affects our health. I’m especially interested when there is evidence to support the ideas.

As the American diet has changed in the past few decades, we have been gaining weight. It is also true that we are seeing more diseases – especially those that have an inflammatory component. Inflammation is when the body responds to things that shouldn’t be there – like an infection or a chemical – and the body sends cells to the area to fight them off. This can lead to pain and swelling, among other things. Some diseases caused by inflammation have “itis” at the end – arthritis, colitis, bronchitis, etc.

Is it possible that the food we eat is causing some of these diseases that are due to inflammation?

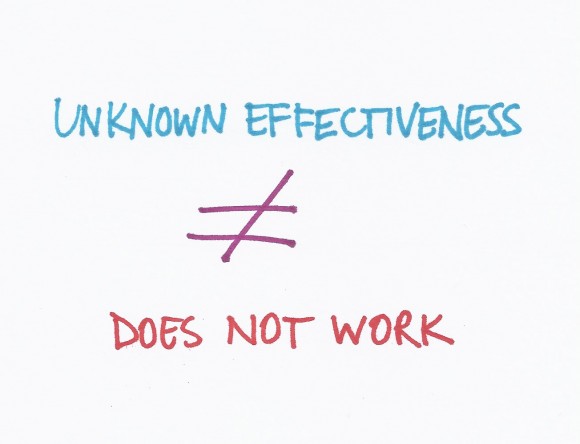

Many commonly used treatments may not work

A Washington Post WonkBlog piece entitled “Surprise! We don’t know if half our medical treatments work” got a lot of attention in social media circles. The title is a bit misleading but the concepts are really important. First, let me say that I worked at the BMJ for 8 years and was involved with the Clinical Evidence publication that is discussed in the blog so I may be a little biased!

A Washington Post WonkBlog piece entitled “Surprise! We don’t know if half our medical treatments work” got a lot of attention in social media circles. The title is a bit misleading but the concepts are really important. First, let me say that I worked at the BMJ for 8 years and was involved with the Clinical Evidence publication that is discussed in the blog so I may be a little biased!

The way doctors determine if medical treatments work is to perform research studies called randomized controlled trials (RCTs). These are studies where half the patients get a treatment and half get a placebo (or inactive treatment like a sugar pill) but the patients and the researchers do not know who is getting what. After a period of time (could be years), the researchers look at the results and figure out which group did better.