Tag: bacteria

The Microbiota Vault

In January, I moderated a symposium that was based (virtually) in Peru to discuss preserving both the culture and the microbes of its indigenous people. Similar events, organized by the Global Microbiome Network, are planned in other regions around the world where indigenous populations still exist. Why is this important?

In January, I moderated a symposium that was based (virtually) in Peru to discuss preserving both the culture and the microbes of its indigenous people. Similar events, organized by the Global Microbiome Network, are planned in other regions around the world where indigenous populations still exist. Why is this important?

I’ve written before (here and here) about the importance of a healthy microbiota – those trillions of microbes that live in and on our bodies, especially in the gut. The collection of genes inside these microbial cells in called the microbiome. There are more genes in the microbiome than there are genes in the human body. These microbial genes perform necessary functions in our bodies like helping to digest food and producing vitamins. If some of these microbes die off, the functions performed by their genes are also lost. The loss of microbial species in our guts appears to be playing a role in the rise in chronic diseases that we are seeing in industrialized society. More and more research studies confirm the role of the microbiome in health and disease.

Is the microbiome the key to health?

Interest in the microbiome – those trillions of bugs (bacteria and other microorganisms) in your gut – is increasing and according to an article in the NY Times, drug companies are trying to get in on the action.

Interest in the microbiome – those trillions of bugs (bacteria and other microorganisms) in your gut – is increasing and according to an article in the NY Times, drug companies are trying to get in on the action.

As I’ve written before, these bugs may be important in the development of chronic disease leading to the possibility that you can “transplant” healthier bugs into someone with a disease. In fact, transferring the feces (poop) from one person to another has been shown to cure cases of Clostridioides difficile (C. diff) colitis (a life threatening infection of the gut caused by overuse of antibiotics). This is called fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). Studies are ongoing to see if FMT can be used to treat inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and other chronic conditions. But there are a limited number of places doing FMT so people are doing their own transplants by harvesting the feces of a friend or family member and using a home blender (I’ll spare you any additional details but the DIY instructions are readily available online).

The bugs we live with

Remember in elementary school science class when we put samples of our hair and saliva in Petri dishes to see what grew? We even used cotton swabs to test the surfaces of our desks and bacteria grew in a few days. These experiments were designed to show us that we have lots of bacteria inside and on our bodies – and all around us. There are microbes (bacteria, viruses, fungi, etc.) everywhere in our “built environment” – the buildings we live and work in – as seen in this incredible animation.

Remember in elementary school science class when we put samples of our hair and saliva in Petri dishes to see what grew? We even used cotton swabs to test the surfaces of our desks and bacteria grew in a few days. These experiments were designed to show us that we have lots of bacteria inside and on our bodies – and all around us. There are microbes (bacteria, viruses, fungi, etc.) everywhere in our “built environment” – the buildings we live and work in – as seen in this incredible animation.

Research suggests that the microbes in our guts play an important role in the development of disease. This collection of organisms, referred to as the microbiome (although technically the collection of organisms is called the microbiota and the genes of those organisms are called the microbiome), may play a role in the development of many diseases including diabetes, obesity, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, allergies, Crohn’s disease, autism and cancer.

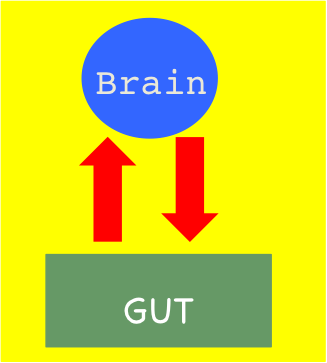

The gut and the brain

We don’t normally think about the gut and the brain being connected. And yet many of us have gotten a stomach ache, nausea or diarrhea from stress or a feeling of “butterflies” from excitement. Or we may experience pleasure from certain foods or feel a need to eat when under stress.

We don’t normally think about the gut and the brain being connected. And yet many of us have gotten a stomach ache, nausea or diarrhea from stress or a feeling of “butterflies” from excitement. Or we may experience pleasure from certain foods or feel a need to eat when under stress.

The vagus nerve travels between the brain and other organs in the body and can transmit messages in both directions. The brain can send messages to the gut through chemicals (called neurotransmitters). The gut has its own nervous system (called the enteric nervous system or ENS) that controls digestion. But scientists now think that the ENS can also produce neurotransmitters to send to the brain.

The big question is whether the gut can actually cause symptoms and diseases of the nervous system.

FODMAPs

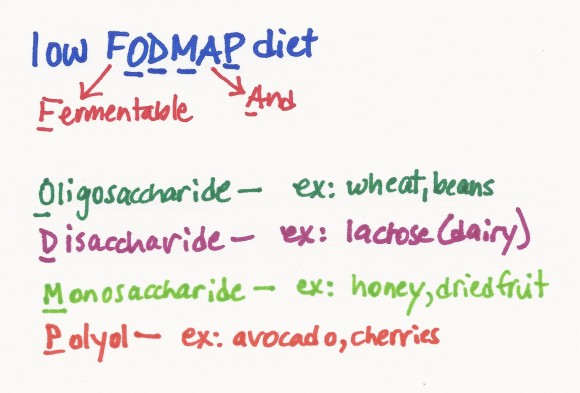

A few weeks ago, I was asked if I knew anything about the low FODMAP diet as a treatment for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). I was sure this was yet another fad diet (or that the name was misspelled – seemed like FOD should be FOOD, right?) .

A few weeks ago, I was asked if I knew anything about the low FODMAP diet as a treatment for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). I was sure this was yet another fad diet (or that the name was misspelled – seemed like FOD should be FOOD, right?) .

Imagine my surprise when I found detailed information about the diet and its use in treating irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) on the Stanford Health Care website. Irritable bowel syndrome is a chronic condition that causes abdominal pain, bloating, gas, diarrhea and other symptoms in the gut. It turns out that FODMAP is an acronym for Fermentable Oligosaccharide, Disaccharide, Monosaccharides and Polyol. All of these substances are found in certain foods and are types of carbohydrates. Researchers in Australia found that these carbohydrates are not well absorbed by the small intestine in people with IBS. As a result, the substances stay in the gut rather than being used by the body and they pull water into the gut. The FODMAPs can also be fermented by the bacteria in the gut which produces gas. All of this can lead to a bloating feeling, pain and other symptoms.

The dark side of bacteria

Bacteria are our friends…but not all the time.

While I believe that we need to keep the bacteria in our bodies happy and that the improved cleanliness of modern life may be causing problems, there is also no question that bacteria are our enemies as well. You don’t have to look very far to see examples of how bacteria can cause serious illness or even death – meningococal meningitis, pneumococcal pneumonia, salmonella and tuberculosis to name a few. In most cases, antibiotics are required to treat these infections (or vaccines to prevent the infections).