Are screening tests good for you?

If we had a serious disease, we’d like to learn about it before we even had symptoms (so we could get started on treatment). And most of us would like to know if we were at risk of developing a serious disease (so we could make changes to prevent the disease). Right?

Two recent articles in the NY Times point out the problems with screening tests.

Are we in Belarus?

I spent much of last week trying to sort out the bills for the medication my daughter receives by infusion every 2 months. I’ve written before about the facility fees that many hospitals charge patients to inflate their bills and about how hospital bills are impossible for patients to understand. Because the facility fees doubled our out-of-pocket expenses, we applied to a program run by the pharmaceutical company, that reimburses patients for up to $6000 per year for drug costs.

I spent much of last week trying to sort out the bills for the medication my daughter receives by infusion every 2 months. I’ve written before about the facility fees that many hospitals charge patients to inflate their bills and about how hospital bills are impossible for patients to understand. Because the facility fees doubled our out-of-pocket expenses, we applied to a program run by the pharmaceutical company, that reimburses patients for up to $6000 per year for drug costs.

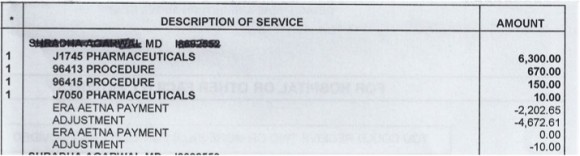

The drug company program requires that the patient send copies of the Explanation of Benefits (EOB) from the insurance company along with the bill from the hospital after each infusion. Unfortunately, neither the insurance company nor the hospital includes the name of the drug in their paperwork so the reimbursement was denied by the drug company. After many attempts I was able to get an itemized bill from the hospital (although they made it clear that I would have to call each time I needed one in the future). The reimbursement for one infusion was finally issued – but it was put on a Mastercard that could only be used for payment of future infusions. After many weeks, I finally found a person in the infusion center who agreed to help me figure out how to spend the money that was already on the Mastercard.

Giving thanks

As Thanksgiving approaches, I am thinking a lot about the death of my father in early November 2011. I am thankful that my mother and I had the strength to bring him home to die with dignity, surrounded by his family. I feel blessed that my father lived a long, productive life and that he did not spend his last weeks or months in a hospital bed receiving treatment to prolong his life but not necessarily prolong the life he wanted to live.

As Thanksgiving approaches, I am thinking a lot about the death of my father in early November 2011. I am thankful that my mother and I had the strength to bring him home to die with dignity, surrounded by his family. I feel blessed that my father lived a long, productive life and that he did not spend his last weeks or months in a hospital bed receiving treatment to prolong his life but not necessarily prolong the life he wanted to live.

Death is not the enemy of life, it is a part of life. As Steve Jobs said in a commencement address at Stanford University in 2005:

No one wants to die. Even people who want to go to heaven don’t want to die to get there. And yet death is the destination we all share. No one has ever escaped it.

And yet, we often fight it, even when there is little hope of meaningful life.

Who makes the best medical student?

As I begin my 4th year interviewing prospective medical students, I am reminded of how challenging it is to figure out which applicants will possess all of the characteristics that I would want in my own doctor.

There is little question that we need to rethink the way we educate medical students to meet the needs of a changing healthcare system. Medicine is no longer a paternalistic practice where the doctor tells the patient what to do. Not only are patients becoming more empowered to participate in the own care, but they also have information at their fingertips about their own conditions and can access online discussion groups to talk with other patients about their shared experiences. The blog Wing of Zock looks at innovative ways to redesign medical education.

Making patients pay more

Medical bills are not designed to make sense to the patient. In fact, as I’ve written before, they are almost impossible to understand, even when the charges are explained by the billing office.

So it’s pretty easy for hospitals to add charges to the bill without the patient really knowing. One popular way is to add a “facility fee”.

My daughter in on a medication that is given once every 2 months. She goes to the doctors’ office building that is connected to an academic medical center where the medication is given through an IV over the course of a few hours. The staff members in the infusion center know her well and her doctor often stops by to say hello while she is there.

Redefining the care team

When I was in clinical practice as an infectious diseases specialist, most of my patients were very sick and hospitalized but I saw a small number of outpatients as well. They were often people who had nonspecific complaints and were convinced that they had a chronic infection that their doctors were missing. They often arrived with numerous records – laboratory tests results, x-ray reports and consultation letters from other doctors.

When I was in clinical practice as an infectious diseases specialist, most of my patients were very sick and hospitalized but I saw a small number of outpatients as well. They were often people who had nonspecific complaints and were convinced that they had a chronic infection that their doctors were missing. They often arrived with numerous records – laboratory tests results, x-ray reports and consultation letters from other doctors.

While it is certainly possible that these patients had an infectious disease that we don’t know about yet or that I had missed, many of them had significant stress in their lives – housing issues, trouble with their children or spouses, difficulites at work, etc. There is a lot of evidence that stress can lead to serious health issues including heart attacks.

The wisdom of patients

Last week was the third anniversary of the death of my lifelong friend, Judy Feder. In 2001, Judy was diagnosed with Stage IV breast cancer at the age of 45.

Last week was the third anniversary of the death of my lifelong friend, Judy Feder. In 2001, Judy was diagnosed with Stage IV breast cancer at the age of 45.

I was involved in a health internet start-up at the time and knew about Gilles Frydman’s pioneering work in creating a collection of online patient communities called the Association of Cancer Online Resources (ACOR). Judy joined the group for patients with metastatic breast cancer. She embraced online communications (perhaps at least in part because she was a public relations professional) and participated in a second breast cancer online community called BC Mets as well. You can read about her 8-year breast cancer journey in this article in the Journal of Participatory Medicine, the journal of the Society for Participatory Medicine of which she was a founding member.

The power of respect

Last week, I went to see my dermatologist for a full body check to make sure I don’t have melanoma. I showed up for my 3:00pm appointment a few minutes early and the receptionist said in a gruff voice, “You’re late. You had a 2:15 appointment. You can wait for the doctor to finish her office hours and be seen at the end of the day if you want”.

Hmmm….that was a little confusing since I had 3:00 in my calendar for many weeks – I made the appointment well in advance knowing that the dermatologist would need extra time for this type of appointment. So I told the receptionist that I thought there must be some mistake and asked if she could check again. By now she was really annoyed with me and said “No, you had a 2:15 appointment and it says right here that they tried to call you to confirm and your phone was out of service.” Now I was sure there was a misunderstanding since they had called to confirm my 3:00 appointment a few days earlier. So I asked her to please check that she had my name right. This time she said that I was correct (but did not offer an apology). She handed me some paperwork and said, in an accusing tone, that I was supposed to come every year and since I hadn’t been there in 3 years I had to fill out the medical history from scratch.

Patient centered billing

My husband and I returned from a weekend away to find a message on our answering machine saying that we owed money to the hospital and that if we didn’t pay it within 10 days, they would send the bill to a collection agency. The message was left on Saturday night and the automated voice said the charges were for cardiology services for our daughter.

My husband and I returned from a weekend away to find a message on our answering machine saying that we owed money to the hospital and that if we didn’t pay it within 10 days, they would send the bill to a collection agency. The message was left on Saturday night and the automated voice said the charges were for cardiology services for our daughter.

Our initial thought was that this was a mistake because: 1) our daughter had not been seen by a cardiologist and 2) we have paid all our bills.

More on technology (and communication)

There is no question that technology can improve the quality of healthcare but it can’t replace the need for good communication.

Dr. Peter Pronovost, a leader in patient safety at Johns Hopkins, wrote a blog post today about how technology can help doctors make the right diagnosis. He cites alarming statistics about how the wrong diagnosis may cause as many as 80,000 deaths each year in the US. He discusses the exciting news that a portable bedside device that is able to measure eye movements, may prove to be useful in emergency rooms to figure out which patients who complain of dizziness are likely to be having a stroke. This development could save lives and also save time and money.

However, in many of the cases of misdiagnosis, the problem is that doctors don’t listen carefully to what patients and their families are saying. They forget that patients are the experts about their own symptoms. Doctors have a tendency to get locked into thinking about a particular diagnosis and may not listen to what patients (and their families) are telling them.