Category: Patients

Are we in Belarus?

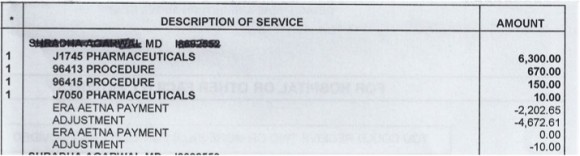

I spent much of last week trying to sort out the bills for the medication my daughter receives by infusion every 2 months. I’ve written before about the facility fees that many hospitals charge patients to inflate their bills and about how hospital bills are impossible for patients to understand. Because the facility fees doubled our out-of-pocket expenses, we applied to a program run by the pharmaceutical company, that reimburses patients for up to $6000 per year for drug costs.

I spent much of last week trying to sort out the bills for the medication my daughter receives by infusion every 2 months. I’ve written before about the facility fees that many hospitals charge patients to inflate their bills and about how hospital bills are impossible for patients to understand. Because the facility fees doubled our out-of-pocket expenses, we applied to a program run by the pharmaceutical company, that reimburses patients for up to $6000 per year for drug costs.

The drug company program requires that the patient send copies of the Explanation of Benefits (EOB) from the insurance company along with the bill from the hospital after each infusion. Unfortunately, neither the insurance company nor the hospital includes the name of the drug in their paperwork so the reimbursement was denied by the drug company. After many attempts I was able to get an itemized bill from the hospital (although they made it clear that I would have to call each time I needed one in the future). The reimbursement for one infusion was finally issued – but it was put on a Mastercard that could only be used for payment of future infusions. After many weeks, I finally found a person in the infusion center who agreed to help me figure out how to spend the money that was already on the Mastercard.

Giving thanks

As Thanksgiving approaches, I am thinking a lot about the death of my father in early November 2011. I am thankful that my mother and I had the strength to bring him home to die with dignity, surrounded by his family. I feel blessed that my father lived a long, productive life and that he did not spend his last weeks or months in a hospital bed receiving treatment to prolong his life but not necessarily prolong the life he wanted to live.

As Thanksgiving approaches, I am thinking a lot about the death of my father in early November 2011. I am thankful that my mother and I had the strength to bring him home to die with dignity, surrounded by his family. I feel blessed that my father lived a long, productive life and that he did not spend his last weeks or months in a hospital bed receiving treatment to prolong his life but not necessarily prolong the life he wanted to live.

Death is not the enemy of life, it is a part of life. As Steve Jobs said in a commencement address at Stanford University in 2005:

No one wants to die. Even people who want to go to heaven don’t want to die to get there. And yet death is the destination we all share. No one has ever escaped it.

And yet, we often fight it, even when there is little hope of meaningful life.

Making patients pay more

Medical bills are not designed to make sense to the patient. In fact, as I’ve written before, they are almost impossible to understand, even when the charges are explained by the billing office.

So it’s pretty easy for hospitals to add charges to the bill without the patient really knowing. One popular way is to add a “facility fee”.

My daughter in on a medication that is given once every 2 months. She goes to the doctors’ office building that is connected to an academic medical center where the medication is given through an IV over the course of a few hours. The staff members in the infusion center know her well and her doctor often stops by to say hello while she is there.

Redefining the care team

When I was in clinical practice as an infectious diseases specialist, most of my patients were very sick and hospitalized but I saw a small number of outpatients as well. They were often people who had nonspecific complaints and were convinced that they had a chronic infection that their doctors were missing. They often arrived with numerous records – laboratory tests results, x-ray reports and consultation letters from other doctors.

When I was in clinical practice as an infectious diseases specialist, most of my patients were very sick and hospitalized but I saw a small number of outpatients as well. They were often people who had nonspecific complaints and were convinced that they had a chronic infection that their doctors were missing. They often arrived with numerous records – laboratory tests results, x-ray reports and consultation letters from other doctors.

While it is certainly possible that these patients had an infectious disease that we don’t know about yet or that I had missed, many of them had significant stress in their lives – housing issues, trouble with their children or spouses, difficulites at work, etc. There is a lot of evidence that stress can lead to serious health issues including heart attacks.

The wisdom of patients

Last week was the third anniversary of the death of my lifelong friend, Judy Feder. In 2001, Judy was diagnosed with Stage IV breast cancer at the age of 45.

Last week was the third anniversary of the death of my lifelong friend, Judy Feder. In 2001, Judy was diagnosed with Stage IV breast cancer at the age of 45.

I was involved in a health internet start-up at the time and knew about Gilles Frydman’s pioneering work in creating a collection of online patient communities called the Association of Cancer Online Resources (ACOR). Judy joined the group for patients with metastatic breast cancer. She embraced online communications (perhaps at least in part because she was a public relations professional) and participated in a second breast cancer online community called BC Mets as well. You can read about her 8-year breast cancer journey in this article in the Journal of Participatory Medicine, the journal of the Society for Participatory Medicine of which she was a founding member.

The power of respect

Last week, I went to see my dermatologist for a full body check to make sure I don’t have melanoma. I showed up for my 3:00pm appointment a few minutes early and the receptionist said in a gruff voice, “You’re late. You had a 2:15 appointment. You can wait for the doctor to finish her office hours and be seen at the end of the day if you want”.

Hmmm….that was a little confusing since I had 3:00 in my calendar for many weeks – I made the appointment well in advance knowing that the dermatologist would need extra time for this type of appointment. So I told the receptionist that I thought there must be some mistake and asked if she could check again. By now she was really annoyed with me and said “No, you had a 2:15 appointment and it says right here that they tried to call you to confirm and your phone was out of service.” Now I was sure there was a misunderstanding since they had called to confirm my 3:00 appointment a few days earlier. So I asked her to please check that she had my name right. This time she said that I was correct (but did not offer an apology). She handed me some paperwork and said, in an accusing tone, that I was supposed to come every year and since I hadn’t been there in 3 years I had to fill out the medical history from scratch.

Patient centered billing

My husband and I returned from a weekend away to find a message on our answering machine saying that we owed money to the hospital and that if we didn’t pay it within 10 days, they would send the bill to a collection agency. The message was left on Saturday night and the automated voice said the charges were for cardiology services for our daughter.

My husband and I returned from a weekend away to find a message on our answering machine saying that we owed money to the hospital and that if we didn’t pay it within 10 days, they would send the bill to a collection agency. The message was left on Saturday night and the automated voice said the charges were for cardiology services for our daughter.

Our initial thought was that this was a mistake because: 1) our daughter had not been seen by a cardiologist and 2) we have paid all our bills.

More on technology (and communication)

There is no question that technology can improve the quality of healthcare but it can’t replace the need for good communication.

Dr. Peter Pronovost, a leader in patient safety at Johns Hopkins, wrote a blog post today about how technology can help doctors make the right diagnosis. He cites alarming statistics about how the wrong diagnosis may cause as many as 80,000 deaths each year in the US. He discusses the exciting news that a portable bedside device that is able to measure eye movements, may prove to be useful in emergency rooms to figure out which patients who complain of dizziness are likely to be having a stroke. This development could save lives and also save time and money.

However, in many of the cases of misdiagnosis, the problem is that doctors don’t listen carefully to what patients and their families are saying. They forget that patients are the experts about their own symptoms. Doctors have a tendency to get locked into thinking about a particular diagnosis and may not listen to what patients (and their families) are telling them.

Technology is bad…and good

During my last year in medical school, I was sitting on a bus on a cold winter day when I realized that my finger tips felt numb. I took off my gloves and watched the color of my fingers go from white to blue to red. I knew from my studies that this was Raynaud’s phenomenon and was caused by the blood vessels in my fingers becoming narrowed (going into spasm) due to the cold. I also knew that this was a relatively common problem in women. Unfortunately, I also knew that it could be a sign of something more serious, such as lupus or rheumatoid arthritis. Medical students are known to be hypochondriacs and I went to see my physician the next day convinced that I was gravely ill. He was an incredibly warm and caring person and explained to me that he didn’t think it made sense to test for all the things it could be and that we should just see what happened over time. He reassured me and I felt better. This was doctor-patient communication at its best.

I believe strongly that the relationship between a doctor and a patient can lead to healing by itself. And there is little question that doctors have less time to listen to us than they did many years ago – in fact some studies suggest that it is as little as 7 or 8 minutes on average. And with more diagnostic tests available – specialized x-rays, CT scans, MRIs, etc – doctors are more likely to perform tests than take the time to listen to us. If they are using an electronic health record, they may seem more interested in entering information than in hearing what we have to say.

Does food cause inflammation?

I am fascinated by food – what makes us eat the food we eat and how it affects our health. I’m especially interested when there is evidence to support the ideas.

As the American diet has changed in the past few decades, we have been gaining weight. It is also true that we are seeing more diseases – especially those that have an inflammatory component. Inflammation is when the body responds to things that shouldn’t be there – like an infection or a chemical – and the body sends cells to the area to fight them off. This can lead to pain and swelling, among other things. Some diseases caused by inflammation have “itis” at the end – arthritis, colitis, bronchitis, etc.

Is it possible that the food we eat is causing some of these diseases that are due to inflammation?