Category: Communication

More on technology (and communication)

There is no question that technology can improve the quality of healthcare but it can’t replace the need for good communication.

Dr. Peter Pronovost, a leader in patient safety at Johns Hopkins, wrote a blog post today about how technology can help doctors make the right diagnosis. He cites alarming statistics about how the wrong diagnosis may cause as many as 80,000 deaths each year in the US. He discusses the exciting news that a portable bedside device that is able to measure eye movements, may prove to be useful in emergency rooms to figure out which patients who complain of dizziness are likely to be having a stroke. This development could save lives and also save time and money.

However, in many of the cases of misdiagnosis, the problem is that doctors don’t listen carefully to what patients and their families are saying. They forget that patients are the experts about their own symptoms. Doctors have a tendency to get locked into thinking about a particular diagnosis and may not listen to what patients (and their families) are telling them.

Technology is bad…and good

During my last year in medical school, I was sitting on a bus on a cold winter day when I realized that my finger tips felt numb. I took off my gloves and watched the color of my fingers go from white to blue to red. I knew from my studies that this was Raynaud’s phenomenon and was caused by the blood vessels in my fingers becoming narrowed (going into spasm) due to the cold. I also knew that this was a relatively common problem in women. Unfortunately, I also knew that it could be a sign of something more serious, such as lupus or rheumatoid arthritis. Medical students are known to be hypochondriacs and I went to see my physician the next day convinced that I was gravely ill. He was an incredibly warm and caring person and explained to me that he didn’t think it made sense to test for all the things it could be and that we should just see what happened over time. He reassured me and I felt better. This was doctor-patient communication at its best.

I believe strongly that the relationship between a doctor and a patient can lead to healing by itself. And there is little question that doctors have less time to listen to us than they did many years ago – in fact some studies suggest that it is as little as 7 or 8 minutes on average. And with more diagnostic tests available – specialized x-rays, CT scans, MRIs, etc – doctors are more likely to perform tests than take the time to listen to us. If they are using an electronic health record, they may seem more interested in entering information than in hearing what we have to say.

Does food cause inflammation?

I am fascinated by food – what makes us eat the food we eat and how it affects our health. I’m especially interested when there is evidence to support the ideas.

As the American diet has changed in the past few decades, we have been gaining weight. It is also true that we are seeing more diseases – especially those that have an inflammatory component. Inflammation is when the body responds to things that shouldn’t be there – like an infection or a chemical – and the body sends cells to the area to fight them off. This can lead to pain and swelling, among other things. Some diseases caused by inflammation have “itis” at the end – arthritis, colitis, bronchitis, etc.

Is it possible that the food we eat is causing some of these diseases that are due to inflammation?

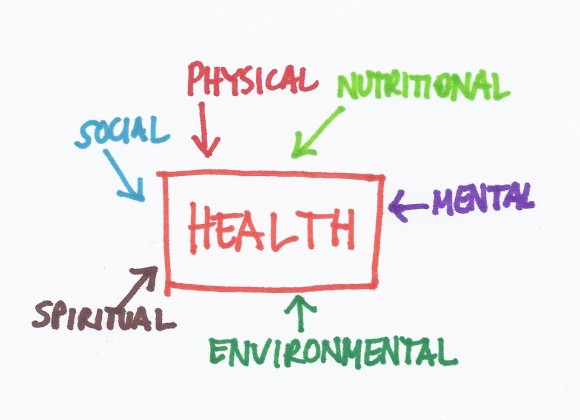

The whole patient

During my internship, I had an 18 year old patient with diabetes who I followed in my outpatient clinic (let’s call him Sam). He was first diagnosed at age 3 and had many hospitalizations thereafter for his poorly controlled diabetes. On one of these admissions, he arrived in the emergency room unconscious and near death because he hadn’t been taking his insulin. I happened to be on-call and stayed up with him all night managing his care. This required drawing blood tests every hour, adjusting medications, giving nutrients and fluids, etc. In the morning I had to present the situation to the physician in charge of my team at morning rounds. I proudly discussed how I had taken care of all of Sam’s problems throughout the night and how well he now looked. The senior physician asked me and the other interns and residents on our the team what the diagnosis was in this patient. We all looked at him like he was crazy since we had been talking about Sam’s diabetic emergency for the past 15 minutes. Then he told us that he thought the diagnosis was “communication failure”. Then we were convinced that he was crazy.

During my internship, I had an 18 year old patient with diabetes who I followed in my outpatient clinic (let’s call him Sam). He was first diagnosed at age 3 and had many hospitalizations thereafter for his poorly controlled diabetes. On one of these admissions, he arrived in the emergency room unconscious and near death because he hadn’t been taking his insulin. I happened to be on-call and stayed up with him all night managing his care. This required drawing blood tests every hour, adjusting medications, giving nutrients and fluids, etc. In the morning I had to present the situation to the physician in charge of my team at morning rounds. I proudly discussed how I had taken care of all of Sam’s problems throughout the night and how well he now looked. The senior physician asked me and the other interns and residents on our the team what the diagnosis was in this patient. We all looked at him like he was crazy since we had been talking about Sam’s diabetic emergency for the past 15 minutes. Then he told us that he thought the diagnosis was “communication failure”. Then we were convinced that he was crazy.

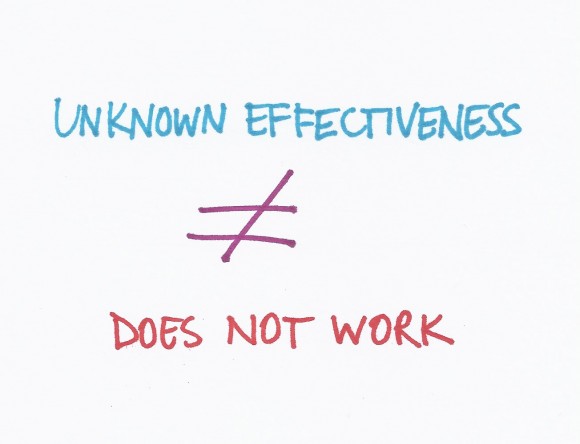

Many commonly used treatments may not work

A Washington Post WonkBlog piece entitled “Surprise! We don’t know if half our medical treatments work” got a lot of attention in social media circles. The title is a bit misleading but the concepts are really important. First, let me say that I worked at the BMJ for 8 years and was involved with the Clinical Evidence publication that is discussed in the blog so I may be a little biased!

A Washington Post WonkBlog piece entitled “Surprise! We don’t know if half our medical treatments work” got a lot of attention in social media circles. The title is a bit misleading but the concepts are really important. First, let me say that I worked at the BMJ for 8 years and was involved with the Clinical Evidence publication that is discussed in the blog so I may be a little biased!

The way doctors determine if medical treatments work is to perform research studies called randomized controlled trials (RCTs). These are studies where half the patients get a treatment and half get a placebo (or inactive treatment like a sugar pill) but the patients and the researchers do not know who is getting what. After a period of time (could be years), the researchers look at the results and figure out which group did better.

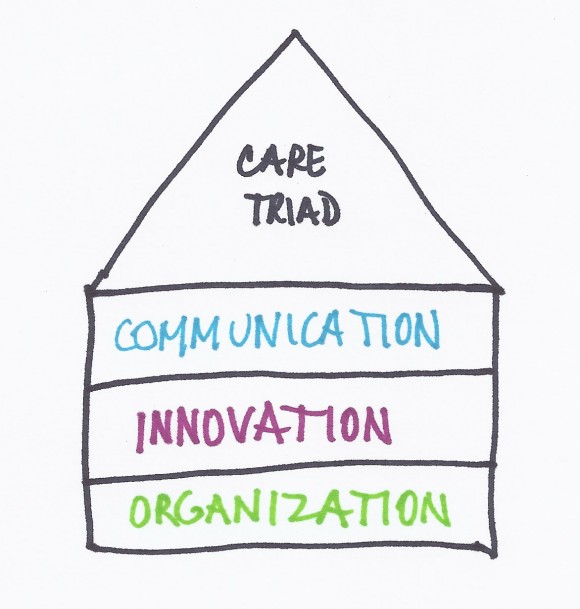

Communication, Innovation and Organization

The Care Triad doesn’t really work without three important foundations – communication, innovation and organization.

The Care Triad doesn’t really work without three important foundations – communication, innovation and organization.

Communication requires that all members of the healthcare team understand that the patient is the most important person on the team. Patients should be spoken to in a respectful way starting with the person who sits at the welcome desk. Doctors need to learn to translate complicated medical information into ways that patients can understand it and patients need to learn to ask questions when they don’t understand what the doctor is saying. Doctors (and other members of the healthcare team), patients and family members also need to learn to talk openly about the end of life. Patients may also find it helpful to communicate with each other in online communities. Both doctors and patients need to learn to use social media to help themselves and each other, recognizing the power of personal experiences.