Category: Communication

COVID-19 in a nutshell

As a former hospital-based infectious diseases physician, I have been reading everything I can about the coronavirus pandemic. Because this is a new coronavirus not previously seen in humans, the World Health Organization gave the disease the name COVID-19, which stands for Coronavirus Disease 2019. While there is a flurry of high quality up-to-the-minute, information available, especially on Twitter, it is challenging to get the most important information in one place. Based on questions I am getting, here is my attempt to provide a quick overview and answer the key questions.

Read morePatient-collected data

In April 2018, I participated in the 2018 Quantified Self (QS) Symposium on Cardiovascular Diseases held in San Diego. I was reminded of that session several weeks ago while attending the 2nd Annual Meeting of the Society for Participatory Medicine. In both conferences I was struck by the power of patients’ observations and measurements to manage their own diseases.

In April 2018, I participated in the 2018 Quantified Self (QS) Symposium on Cardiovascular Diseases held in San Diego. I was reminded of that session several weeks ago while attending the 2nd Annual Meeting of the Society for Participatory Medicine. In both conferences I was struck by the power of patients’ observations and measurements to manage their own diseases.

I first learned about the Quantified Self movement a few years ago while reading about Larry Smarr, an astrophysicist and computer scientist who started tracking his own exercise and weight but ultimately began expanding his self-tracking to include blood tests when he was told he had “pre-diabetes”. He ultimately diagnosed his own Crohn’s disease long before he had any symptoms based on analyzing his own blood and stool tests (including twice weekly stool microbiome analysis). He has since published a how-to guide in a biotechnology journal and participated in planning his own bowel resection for Crohn’s disease in 2016.

Hospital centered care

Healthcare decisions are increasingly driven by efficiency and economic factors, even at the end of life. This was brought home to me several months ago with my mother’s death after a short hospitalization for a lung infection.

Healthcare decisions are increasingly driven by efficiency and economic factors, even at the end of life. This was brought home to me several months ago with my mother’s death after a short hospitalization for a lung infection.

Because I was planning to be on vacation during the time of her hospitalization, I was able to be at her side pretty much full time, allowing me a front row seat to a series of decisions that were based on efficiency and hospital reputation rather than patient care.

Follow the money

A few days after my success getting insurance coverage for a 3-month supply of my daughter’s specialty medication, I learned that my husband’s employer was switching to a new specialty pharmacy. This meant that a new organization was now handling all the logistics of getting the drug to may daughter – the paper work, the shipping, collecting of co-pays, etc.

A few days after my success getting insurance coverage for a 3-month supply of my daughter’s specialty medication, I learned that my husband’s employer was switching to a new specialty pharmacy. This meant that a new organization was now handling all the logistics of getting the drug to may daughter – the paper work, the shipping, collecting of co-pays, etc.

While this was very frustrating news, it was not surprising. Specialty drug spending has increased dramatically in recent years. While there is no standard definition of specialty drugs, these are the high-priced drugs (> $600/month) that are often given by injection and are used to treat serious inflammatory conditions (like rheumatoid arthritis or Crohn’s disease), infections (like HIV and hepatitis C) and many types of cancer. These drugs are often amazing – they save lives and improve symptoms in people who would have suffered greatly in the past. Sadly, companies are competing to make money from these high-priced drugs.

It is easy to blame drug companies for the high price of specialty drugs but they are not the only ones who make money on these drugs.

What about the patient?

My 85-year-old mother was recently hospitalized and the experience was a great example of how far our healthcare system has come and how far it still needs to go.

My 85-year-old mother was recently hospitalized and the experience was a great example of how far our healthcare system has come and how far it still needs to go.

The good news is that she only required 2 days in the hospital, had no complications, felt dramatically better at discharge and felt “cared for” during her hospitalization.

Here are a few things that were great: everyone we encountered was very nice, she received a printed record of her hospitalization when she was discharged (it didn’t contain much useful information but that’s a separate issue) and she was helped to sign up for access to the hospital portal so she could review her records online.

In short, the customer service was excellent. However, there were 2 important failures to see things through her eyes – one on admission and one on discharge.

How to pick a surgeon

Several years ago a close friend asked me to recommend a surgeon for an elective procedure. I told her I had a colleague with a great bedside manner who also had great technical skills. He was absolutely the person I would go to if I needed general surgery. My friend went to see him but ended up using a different surgeon. When I asked her what she liked about the other guy, she said that he told her that he was “the best” surgeon to perform the procedure. She didn’t like his personality but he instilled her with confidence.

Several years ago a close friend asked me to recommend a surgeon for an elective procedure. I told her I had a colleague with a great bedside manner who also had great technical skills. He was absolutely the person I would go to if I needed general surgery. My friend went to see him but ended up using a different surgeon. When I asked her what she liked about the other guy, she said that he told her that he was “the best” surgeon to perform the procedure. She didn’t like his personality but he instilled her with confidence.

The truth is that there is no single “best” surgeon for everyone. And there are many factors that go into picking a surgeon: insurance issues, convenience, etc. And there are advantages to going to a surgeon who works well with our primary care physician (communication) and in having surgery in a place that has an electronic medical record that our primary care physician can access (coordination of care). But the most important thing is how skilled the surgeon is at performing the surgery we need. How do we figure that out? The short answer is that we don’t.

Using art to heal

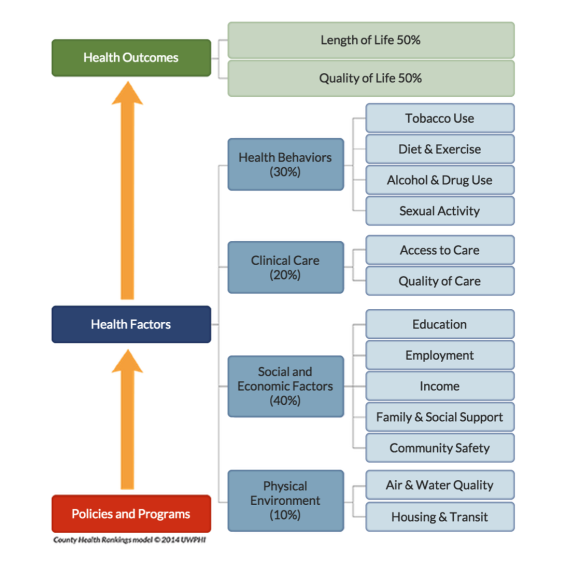

Because Health is Life, our lifestyles are just as important to our health as going to the doctor or taking our medicines. In a paper published June 30, 2015 in the Annals of Internal Medicine, a study looking at survey data found that half the heart disease deaths in the US from 2009-2010 were caused by 5 factors all of which can be modified through healthy behavior: smoking, obesity, high cholesterol, diabetes and high blood pressure. But many of these behaviors are difficult to change and are influenced by our families, our culture and our community.

Because Health is Life, our lifestyles are just as important to our health as going to the doctor or taking our medicines. In a paper published June 30, 2015 in the Annals of Internal Medicine, a study looking at survey data found that half the heart disease deaths in the US from 2009-2010 were caused by 5 factors all of which can be modified through healthy behavior: smoking, obesity, high cholesterol, diabetes and high blood pressure. But many of these behaviors are difficult to change and are influenced by our families, our culture and our community.

This picture shows that clinical care by doctors and hospitals accounts for only about 20% of health outcomes. The picture comes from a project called County Health Rankings developed by the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute (and supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation) that looks at health by county in the US. Addressing factors like cigarette smoking, income, education, employment, housing and clear air can help make communities healthier places to live.

We need to find ways to build healthier communities and the arts may be one way to accomplish this.

Listen up

Like millions of other people, I became hooked on “Serial”, the 12 episode podcast series that launched in late 2014 investigating the murder of a teenage girl in Baltimore in 1999 (that included phone conversations from prison with her personable ex-boyfriend who was convicted of the crime).

Like millions of other people, I became hooked on “Serial”, the 12 episode podcast series that launched in late 2014 investigating the murder of a teenage girl in Baltimore in 1999 (that included phone conversations from prison with her personable ex-boyfriend who was convicted of the crime).

I don’t listen to a lot of podcasts but this was different. It was chatty, used a lot of personal stories and was the perfect thing to listen to while driving, walking or cooking. And I couldn’t wait for the next episode (nor could my 84-year-old mother or my 20-something daughters). Devoting over 10 hours to the program was not only easy but enjoyable. In the process we listeners also learned stuff – about the workings of the legal system, the nature of truth, the problems with first-hand accounts, the limitations of memory and much more.

It was like nothing I had ever experienced before and got me thinking about how we could use a similar strategy in healthcare.

Vaccines and trust

Many years ago I worked in a travel clinic advising people about the immunizations they needed before visiting other countries. Sometimes shots were required for entry into a country, such as the yellow fever vaccine. But we also made sure that MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) and other vaccines were up-to-date. The reason was that while immunizations have been very successful in getting rid of measles (and other childhood illnesses) in the US, many countries still have outbreaks. The booster shots were not necessary in the US because we no longer had cases of measles. Until now.

Many years ago I worked in a travel clinic advising people about the immunizations they needed before visiting other countries. Sometimes shots were required for entry into a country, such as the yellow fever vaccine. But we also made sure that MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) and other vaccines were up-to-date. The reason was that while immunizations have been very successful in getting rid of measles (and other childhood illnesses) in the US, many countries still have outbreaks. The booster shots were not necessary in the US because we no longer had cases of measles. Until now.

We are seeing cases of measles (and other childhood illnesses) again because parents are increasingly refusing to get their kids vaccinated. The current outbreak of measles in California is causing a lot of public debate about how to force people to get their kids vaccinated. While we may need to find new ways to enforce vaccination, we also need to restore trust – people increasingly don’t trust doctors, pharmaceutical companies, government agencies or payers.

Health is life

When I was an infectious diseases specialist, most of the patients I saw were hospital inpatients but I also saw a few outpatients. They came to see me because of weeks or months of symptoms that their doctors couldn’t figure out and were often worried that they had a mysterious infection that was hard to diagnose. All of these patients had real symptoms – they were extremely tired, had headaches, muscle pains and sore throats. They generally arrived with stacks of medical records – numerous lab tests and notes from other doctors. I also noticed that many of them had serious “real life” problems – bad marriages, difficulties at work, housing problems, sick relatives and more. Perhaps they really did have an infection that I couldn’t find but I also began to wonder if their symptoms were caused by the stress.

My intuition was that many of these patients would benefit from speaking with a social worker, marriage counselor, psychologist, an expert in finding affordable housing or a financial planner. Unfortunately, these services were not part of our health care system. I suspected that many of my patients would get better if we were able to treat the whole patient, not just the symptoms.