The whole patient

During my internship, I had an 18 year old patient with diabetes who I followed in my outpatient clinic (let’s call him Sam). He was first diagnosed at age 3 and had many hospitalizations thereafter for his poorly controlled diabetes. On one of these admissions, he arrived in the emergency room unconscious and near death because he hadn’t been taking his insulin. I happened to be on-call and stayed up with him all night managing his care. This required drawing blood tests every hour, adjusting medications, giving nutrients and fluids, etc. In the morning I had to present the situation to the physician in charge of my team at morning rounds. I proudly discussed how I had taken care of all of Sam’s problems throughout the night and how well he now looked. The senior physician asked me and the other interns and residents on our the team what the diagnosis was in this patient. We all looked at him like he was crazy since we had been talking about Sam’s diabetic emergency for the past 15 minutes. Then he told us that he thought the diagnosis was “communication failure”. Then we were convinced that he was crazy.

During my internship, I had an 18 year old patient with diabetes who I followed in my outpatient clinic (let’s call him Sam). He was first diagnosed at age 3 and had many hospitalizations thereafter for his poorly controlled diabetes. On one of these admissions, he arrived in the emergency room unconscious and near death because he hadn’t been taking his insulin. I happened to be on-call and stayed up with him all night managing his care. This required drawing blood tests every hour, adjusting medications, giving nutrients and fluids, etc. In the morning I had to present the situation to the physician in charge of my team at morning rounds. I proudly discussed how I had taken care of all of Sam’s problems throughout the night and how well he now looked. The senior physician asked me and the other interns and residents on our the team what the diagnosis was in this patient. We all looked at him like he was crazy since we had been talking about Sam’s diabetic emergency for the past 15 minutes. Then he told us that he thought the diagnosis was “communication failure”. Then we were convinced that he was crazy.

In retrospect, he was right but it would take me years to realize this. The real problem in this case was that Sam was not engaged in his own care and was not motivated to follow his diet, take his insulin and manage his diabetes. While I knew that he lived in poverty with a single mother, I barely spoke with him about life at home or how he was coping with his illness. Unless we figured out how to improve his family situation, deal with his emotional issues and engage him in his own care, he was going to continue to come back to the emergency room gravely ill. We needed to learn to treat the whole patient and not the disease.

This became more obvious to me when I started a hospital program to manage AIDS patients in the late 1980s. At that time, we really didn’t know a lot about how to treat AIDS and the diagnosis was a virtual death sentence. In those early days of the AIDS epidemic, many of the patients we saw were malnourished and had serious psychological and social issues. For example, we saw many married men with AIDS whose wives did not know they were gay. The only way we could manage these patients was to develop a team approach that included clergy members, doctors, nurses, occupational therapists, physical therapists, social workers, nutritionists, etc. The patients were the most important member of the team, guiding the issues that were most important to them. We worked together to make the patients as healthy as possible with a goal of healing even though the medical issues themselves were not curable.

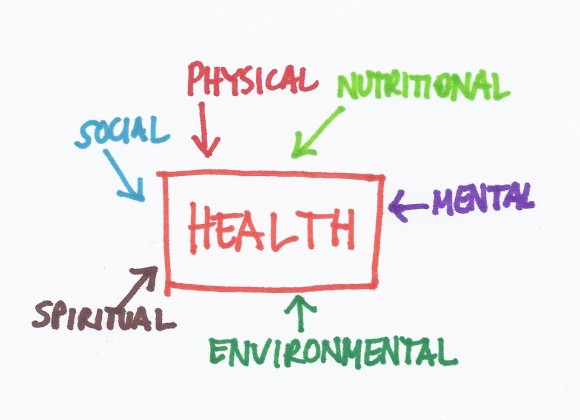

Being healthy means that your social, spiritual, nutritional, environmental and mental issues are managed in addition to your physical ones. Our current healthcare system is not designed to treat the whole person but we will get there if we continue to see this as an important goal. It will require redesigning the education of medical students and other health professionals to think differently about health and disease.

2 thoughts on “The whole patient”